|

Water Wheel History

Water wheel history dates back to about 4000 B.C. Water wheels employed the first method of creating mechanical energy that replaced humans and animals. Below we explore the history of water wheels by region.

Ancient Mesopotamia In water wheel history recorded by ancient Mesopotamia, irrigation machines are referred to in Babylonian inscriptions, but without details on their construction, suggesting that water power had been harnessed for irrigation purposes. The primitive use of water-rotated wheels may date back to Sumerian times, with references to a "Month for raising the Water Wheels", though it is not known whether these wheels were turned by the flow of a river.

Ancient India The early water wheel history of the watermill in India is obscure. Ancient Indian texts dating back to the 4th century BC refer to the term cakkavattaka (turning wheel), which commentaries explain as arahatta-ghati-yanta (machine with wheel-pots attached). On this basis, Joseph Needham suggested that the machine was a noria. Terry S. Reynolds however, argues that the "term used in Indian texts is ambiguous and does not clearly indicate a water-powered device." Thorkild Schiøler argued that it is "more likely that these passages refer to some type of tread - or hand-operated water-lifting device, instead of a water-powered water-lifting wheel." Irrigation water for crops was provided by using water raising wheels, some driven by the force of the current in the river from which the water was being raised. This kind of water raising device was used in ancient India. The construction of water works and aspects of water technology in India is described in Arabic and Persian works. During medieval times, the diffusion of Indian and Persian irrigation technologies gave rise to an advanced irrigation system which bought about economic growth and also helped in the growth of material culture. Greco-Roman Mediterranean The earliest clear evidence of a Water wheel comes from the ancient Greece and Asia Minor, being recorded in the work of Apollonius of Perge of c. 240 BC, surviving only in Arabic translation. Mithradates VI Eupator of Pontus had a water mill at his palace at Cabira before 71 BC.[7] In the 1st century BC, the Greek epigrammatist Antipater of Thessalonica was the first to make a reference to the waterwheel, which Lewis has recently argued to be a vertical wheel. Antipater praised it for its use in grinding grain and the reduction of human labour. Modest numbers of water wheels have been identified in various parts of the Greek and Roman World, and they may have once been much more extensive than historians have recognised. Most towns and cities had good aqueducts, and it would not have been difficult to harness part of the supply to driving water wheels for milling, fulling, crushing and sawing wood and stone such as marble.

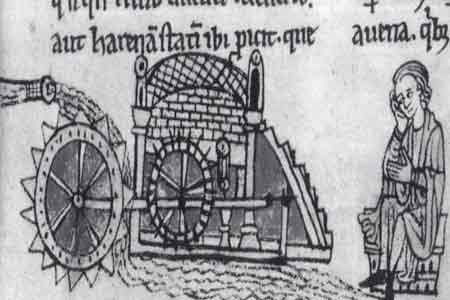

The Romans were known to use waterwheels extensively in mining projects, with enormous Roman-era waterwheels found in places like modern-day Spain. They were reverse overshot water-wheels designed for removing water from mines. A series of overshot mills existed at Barbegal near Arles in southern France where corn was milled for the production of bread. The Roman poet Ausonius mentions a mill for cutting marble on the Moselle. Floating mills were also known from the later Empire, where a wheel was attached to a boat moored in a fast flowing river. Ancient China Two types of hydraulic-powered chain pumps from the Tiangong Kaiwu of 1637, written by the Ming Dynasty encyclopedist Song Yingxing (1587-1666). Chinese water wheel history almost certainly has a separate origin. Early waterwheels were invariably horizontal waterwheels. By at least the 1st century AD, the Chinese of the Eastern Han Dynasty began to use waterwheels to crush grain in mills and to power the piston-bellows in forging iron ore into cast iron. In the text known as the Xin Lun written by Huan Tan about 20 AD (during the usurpation of Wang Mang), it states that the legendary mythological king known as Fu Xi was the one responsible for the pestle and mortar, which evolved into the tilt-hammer and then trip hammer device. Although the author speaks of the mythological Fu Xi, a passage of his writing gives hint that the waterwheel was in widespread use by the 1st century AD in China. In the year 31 AD, the engineer and Prefect of Nanyang, Du Shi, applied a complex use of the waterwheel and machinery to power the bellows of the blast furnace to create cast iron. The inventor Zhang Heng was the first in the water wheel history to apply motive power in rotating the astronomical instrument of an armillary sphere, by use of a waterwheel. The mechanical engineer Ma Jun from Cao Wei once used a waterwheel to power and operate a large mechanical puppet theater for the Emperor Ming of Wei. Islamic Period Muslim engineers employed water wheels as early as the 7th century, excavation of a canal in the Basra region discovered remains of a water wheel dating from this period. Hama in Syria still preserves one of its large wheels, on the river Orontes, although they are no longer in use. The largest had a diameter of about 20 metres and its rim was divided into 120 compartments. Another wheel that is still in operation is found at Murcia in Spain, La Nora, and although the original wheel has been replaced by a steel one, the Moorish system during al-Andalus is otherwise virtually unchanged. The flywheel mechanism, which is used to smooth out the delivery of power from a driving device to a driven machine, was invented by Ibn Bassal of al-Andalus, who pioneered the use of the flywheel in the chain pump and noria. A variety of industrial watermills were used in the Islamic world, including gristmills, hullers, paper mills, sawmills, ship mills, stamp mills, steel mills, sugar mills, and tide mills. By the 11th century, every province throughout the Islamic world had these industrial watermills in operation, from al-Andalus and North Africa to the Middle East and Central Asia. Muslim engineers also used crankshafts and water turbines, gears in watermills and water-raising machines, and dams as a source of water, used to provide additional power to watermills and water-raising machines. Medieval Europe and Modern Cistercian monasteries, in particular, made extensive use of water wheels to power watermills of many kinds. An early example of a very large waterwheel is the still extant wheel at the early 13th century Real Monasterio de Nuestra Senora de Rueda, a Cistercian monastery in the Aragon region of Spain. Grist mills (for corn) were undoubtedly the most common in European water wheel history, but there were also sawmills, fulling mills and mills to fulfill many other labor-intensive tasks. The water wheel remained competitive with the steam engine well into the Industrial Revolution. The main difficulty of water wheels was their inseparability from water. This meant that mills often needed to be located far from population centers and away from natural resources. Water mills were still in commercial use well into the twentieth century, however. Overshot waterwheels are suitable where there is a small stream with a height difference of more than 2 meters, often in association with a small reservoir. Breastshot and undershot wheels can be used on rivers or high volume flows with large reservoirs. The most powerful waterwheel built in the United Kingdom was the 100 hp Quarry Bank Mill Waterwheel near Manchester. A high breastshot design, it was retired in 1904 and replaced with several turbines. It has now been restored and is a museum open to the public. The biggest working waterwheel in mainland Britain has a diameter of 15.4 m and was built by the De Winton company of Caernarfon. It is located within the Dinorwic workshops of the National Slate Museum in Llanberis, North Wales. Modern Hydro-electric dams can be viewed as descendants from water wheel history - as they too take advantage of the movement of water downhill. Return From Water Wheel History To Home Page |